Exploring The Internet’s Domain Name Space

In a previous post, I shared some of my adventures exploring the Swedish domain name space, an adventure that yielded numerous interesting tidbits and got me excited about doing more exploration of DNS data. With nothing to do this weekend, and a rough idea of an interesting data analysis topic, I decided to dig into a security-specific area of DNS records, the configuration of email security records across hundreds of millions of domain names.

In this rather long blog post, I will focus on SPF, DKIM, and DMARC records, all of which are configured using TXT DNS record types, and we will be working with a lot of TXT records, exciting, isn't it? I will walk you through the steps I took to get and prepare the data before digging into insights, findings, and unanswered questions. Grab a cup of coffee or tea, buckle up, and let's dig into more DNS data.

Now that we are all caught up on the basics, let's tackle our first task: getting all the TXT records configured on any of our 193+ million domains.

Getting The Data

Given the number of registered domain names around, collecting TXT records for 193+ million domain names is no small task and there are a couple of options we could get our hands on such data.

Obviously, we could collect this data the old-fashioned way by querying a bunch of public resolvers over a period of time. Unfortunately, such a strategy runs the risk of annoying your ISP, the DNS resolvers, and possibly a bunch of security people who monitor traffic on the internet so it's a no-go for us (not worth the headache for a weekend project).

A second, more reasonable option is to sign up for Domains Monitor's[^ Domains Monitor Homepage: https://domains-monitor.com/] Pro plan[^ Domains Monitor Pricing Plans: https://domains-monitor.com/price/] ($29/month) which provides access to numerous DNS datasets including a detailed list of TXT records for around 193 981 284 domain names. Sure, it costs some money, but $29 is a worthwhile investment considering my affinity for digging into DNS data.

So, I signed up for a new account on Domains Monitor, parted ways with my dear $29, and within minutes, I had access to the various lists offered by the platform many of which piqued my interest but for the purposes of this blog post, we will focus on the detailed TXT records dataset. Okay, We got ourselves a nice CSV file that's around 33Gb uncompressed (6.5Gb when compressed), time to set up the tools I need for my analysis and further shenanigans.

Setting Up The Analysis Machine

Similar to my previous post, I prefer to spin up a beefy VPS when working with huge datasets, as it keeps my local machine tidy and spares me the headache of keeping an eye on my remaining storage or sorting out tooling issues.

For the purposes of this analysis we need a few tools (some of which come preinstalled on most VPSs) including Python3, unzip, curl, and my favourite database tool DuckDB[^ DuckDB: https://duckdb.org/]. Depending on which flavour of Linux you choose (I tend to go with Ubuntu), you can install all the tools using the following commands:

sudo apt update && sudo apt install -y python3 unzip curl duckdbOnce everything is installed, you can use the following curl commands to fetch the required files from Domains Monitor's API (remember to replace YOUR-API-TOKEN with your own API):

curl --output domains-monitor-detailed.zip \

https://domains-monitor.com/api/v1/YOUR-API-TOKEN/get-detailed/full/list/zip/

curl --output domains-monitor-txt-detailed.zip \

https://domains-monitor.com/api/v1/YOUR-API-TOKEN/dnstxt/full/list/zip/The machine is ready, tools are installed, and the data is now ingested into DuckDB, so let's start digging and answer some questions, shall we?

What’s in the Dataset?

Domains Monitor offer numerous lists with varying sizes and details. As of today, their Full detailed domain list includes information on 315 494 341 domains, with the data formatted as follows:

The MX detailed dataset includes 22,249,175 domains, and the detailed TXT dataset includes 193,981,284 domains. These numbers mean that around 61.5% of the full domain list are included in the TXT one, compared to only 7.05% being included in the MX detailed list. My focus for most of this blog post is the detailed TXT dataset, the only exception being the next section covering simple questions (most of which are taken from my previous post) for which I will use the general detailed list of all domains. Now that we have a general idea of what data is available for analysis, let's dig in, and we should start with simple and easy to answer questions. Ready? Let's go.

Simple, Yet Intriguing Questions

I downloaded the detailed list with information on 315,494,341 domains, loaded it into a DuckDB table, and it's now time to answer some simple questions. First one being, what is the distribution of domain names across TLDs (aka how many domain names does each TLD have in our dataset)?

Well, it comes as a surprise to no one that .com came on top with around 159,539,078 domains, followed by .de (157,288,54), .net (122,052,98), .org (118,541,23), and .xyz (80,870,33). The following chart shows the top 25 TLDs by share of domains represented in the data.

How Many Characters Is “Too Many”?

Last time, we learned that a domain label (anything before the TLD) can have up to 63 characters, a domain can have multiple labels, and each domain can have a max of 254 characters across all labels not counting the TLD. So, let's repeat the same analysis to see how long most domains in our data are, and find the longest and shortest domains.

Most domain labels are between 10–25 characters long, with 10 characters being the most common length with over 7.93% of all domain names, followed closely by 8 characters at 7.63%, and 11 characters at 7.59%. The longest domain names are exactly 63 characters long, and the shortest domains are (can you guess?) exactly one character long. So many a.TLD domains out there (actually, that goes for every letter of the alphabet). The following bar chart shows domain name counts grouped by the length of labels (.TLD is not included)

While working on getting the length statistics, I started wondering about distribution of alphabet letters across domain names, and so I queried the table to find out, turns out A (9.22%), E (10.11%), I (7.29%), O (7.15%), and R (6.78%) are very popular where Q (0.32%), J (0.66%), and Z (0.70) might as well not exist.

The data align well with findings presented by the Oxford's Department of Mathematics and Computer Science[^ Letter Frequencies in English: https://mathcenter.oxford.emory.edu/site/math125/englishLetterFreqs/], choosing a domain name is no different from writing an essay or a book. Here is the data presented in a bar chart for easier viewing and interpretation.

What About Names?

In my other post, we looked at how common the top 10 names for boys and girls were among Swedish domains, so I am naturally curious and want to find out how popular names are represented among about much larger dataset. I looked for a reliable list covering the European Union, but after a while, I defaulted back to using the list provided by the Swedish Tax Agency[^ Namn på nyfödda: https://skatteverket.se/4.7da1d2e118be03f8e4f5b9d.html] and added five most popular names in the US into the mix[^ Top 10 Baby Names of 2024: https://www.ssa.gov/oact/babynames/]. The bar chart below shows the data on how many times each name appeared in a domain name.

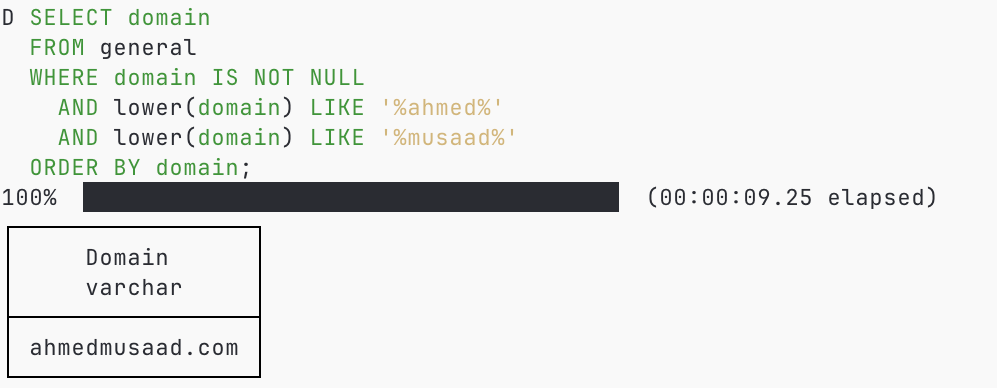

One last indulgence before we look at the TXT data, let's answer one more general (and slightly self-centred) question that needs an answer. How many domain names include my first name, my last name, or both? I know, I know, it's not a good thing to be vain, but I am writing this post, so I get to indulge in a bit of curious vanity, sue me.

As for the question, it turns out a considerable number of domains do include these names. 19,020 domains include Ahmed in the name, 59 include Musaad, and only one single domain includes both names, and that's the domain of this blog. This was a pleasant surprise, and made my day.

Let's Get Technical

So far, we explored some fun, general aspects of our datasets, but the data offers many more layers to unwrap and analyse, many of which are technical details like DNS providers, web servers used, IP addresses, and more. With that in mind, let's switch gears and explore some of these more technical data points, starting with web servers.

For each domain included in Domains Monitor's general detailed list, it includes (whenever possible) the web server used by that domain (think Nginx, Apache, etc.). I crunched the numbers to see which web servers are popular among administrators. As expected, Nginx (37.57%) and Apache (33.08%) are the most popular choice, with Cloudflare coming third (8.78%), litespeed fourth (8.48%), and IIS sixth (5.75%).

The data also lists DNS servers for each domain, which is handy when looking for the most used DNS servers across the internet. After some DuckDB magic, here are the top most common DNS servers across our data:

Finally, let's group domains by country using (when available) the Country column in our dataset. Here are the top 10 countries based on domain counts grouped by country and distilled into a nice bar chart:

There are more layers and data in our general list of domains (e.g. IP addresses, Emails, Phone Numbers, etc.) but let's leave that for another day and switch gear to dig into the TXT dataset and find what surprises it might hold, just waiting to be discovered.

Down The TXT Rabbit Hole We Go

Let's start simple. The TXT data covers 194,207,739 domains, that's about 61.56% of the domains included in the general dataset. With that in mind, how much out of these TXT records does each TLD account for or group by TLDs, how does the hundreds of millions of rows look like? The following graph provides a visual representation of TXT data distribution across TLDs.

Okay, now we know how the data distribution looks like across TLDs, but this cover any TXT records, what about TXT records that mention SPF, DKIM, or DMARC? Moreover, if we replicate the same distribution visualization across TLDs but this time with focus on these three email security records, what does it look like?

Truth be told, I expected that numbers to be skewed, but nothing close to what DuckDB churned out. It's almost impossible to see the DKIM and DMARC numbers in the chart below, as SPF dominates the entire data space. In case you are wondering, about 22,947 domains have all three authentication records configured, shocking but not entirely unexpected.

Before we dig deeper into email authentication methods and their configuration data, let's have a look at site/domain verification records in our dataset. To figure out what site verification records are common, I did some Googling and came upon this post[^ Analyzing DNS TXT Records to Fingerprint Online Service Providers: https://www.netspi.com/blog/technical-blog/network-pentesting/analyzing-dns-txt-records-to-fingerprint-service-providers/] from NetSpi which includes a neat list of common verification records.

Using the verification record syntax from one of the tables[^ Top 25 Service Providers: https://www.netspi.com/blog/technical-blog/network-pentesting/analyzing-dns-txt-records-to-fingerprint-service-providers/#:~:text=Top%2025%20Service%20Providers,-Below], I used DuckDB to crunch the numbers and (drum roll) Google site verification is the most common verification record.

The following chart shows the top 20 most common verification records across the dataset, with the majority being a site or domain verification records. I was pleasantly surprised to see the have-i-been-pwned-verfication records well represented, hopefully more sites will make sure of such wonderful security services.

It's time to dig deeper into SPF, DMARC, and DKIM. If you made it this far, you are a champion, thanks for sticking around, and I promise we are almost done.

Vibe Check: SPF, DKIM, DMARC

Let's dig a bit deeper into SPF records. The first question that popped into my mind was which sending server addresses were topping the charts among all SPF records in our dataset. The following bar chart shows the top 25 included subdomains across the entire dataset. Many of the addresses are totally new to me, and I expected Outlook to top the list, but registrar-servers.com has a choke-hold on that position.

Let's have a look at SPF records first, as they are the most common in our data and also tend to be misconfigured. The SPF mechanism[^ SPF Record Syntax: https://dmarcian.com/spf-syntax-table/] values are probably the trickiest and most misconfiguration-prone part of SPF records. A single character can be the difference between a locked down email authentication setup, and a wide open garage (so to speak).

Let's recap quickly. An -all means that if the sender isn’t explicitly allowed above, it’s not authorized, +all means it's a free-for-all situation where anyone can send emails on behalf of your domain, and a ~all is somewhere in between. Your email might be sent, but it might also be marked as spam or suspicious. So, what does the data says? Here is another chart, can you spot the bar representing +all?

Next stop, DMARC policies and associated DKIM settings[^ What is a DNS DMARC record?: https://www.cloudflare.com/en-gb/learning/dns/dns-records/dns-dmarc-record/]. A DMARC policy can have none, quarantine, or reject in its p parameters. Quarantine indicates that the server should quarantine email that fail the vibe check (aka DKIM and SPF), none pretends DKIM and SPF don't exist and allows emails through even if they fail the checks, and reject, well, it causes emails to be rejected.

Have a look at the chart below, can you spot the problem? Are you feeling a bit stressed? If so, I am sorry, but misery loves company and I can't be the only one sweating over the number of domains using p=none in their DMARC policies.

In addition to the policy setting, DMARC policies can include two additional fields that set the enforcement policy for SPF and DKIM checks, these fields being aspf and adkim. Their value can either be strict or relaxed, think chill vs picky.

Relaxed means SPF/DKIM can still count as aligned as long as it’s under the same parent domain as the From address (so mail.example.com can align with example.com), while strict means it has to be an exact match to the From domain (so only example.com aligns with example.com). As we can see in the chart below, most people seem to favour a relaxed setup, guess technical choices do mirror real life, eh!

What About Swedish Domains?

We have been exploring the overall dataset for a while now, so let's take a detour and look how Swedish domains are doing regarding SPF, DKIM, and DMARC implementation. I ran my DuckDB query, then ran again and again because the results looked strange. Out of 609,134 domains ending in .se, 548,133 have SPF records, 732 have DKIM records, 1119 have DMARC records, and only 92 have all three authentication methods configured in their TXT records. That can't be right, can it?

Perhaps my queries aren't correct, after SQL isn't something I write every day. To double-check, I ran more in-depth text analysis, and the results weren't that different. The new total .se domains count came up to 629,760 domains, 565,493 of which had SPF records, 1140 had DMARC records, and 745 had DKIM records.

I am still not convinced, this can't be right (at least I hope not). Call it naive hope, but I think Swedish domains should be doing better than what the data is showing, and I do intend to dig deeper into the matter, but that's an adventure for another day.

Future Work & Epilogue

There is still much more exploring left to do, countless interesting insights to learn, and much more fun to be had, but this post is already too long and rather dense. So, in the interest of keeping it manageable, let's call it part one, and I promise to write another one with more analysis and insights.

I intend to dig into DNSSEC configuration, validate the SPF, DKIM, and DMARC implementation in Swedish domains, and do more analysis of other security related DNS records. So many things to do, so little time, but hopefully, I will have another free weekend soon to keep digging into the massive world of DNS.

If you have read so far, I commend you on your patience and curiosity. I hope you learned something new or found some intriguing leads that could lead you on your own adventures. If you have questions, feel free to reach out via email or on LinkedIn, I am all too happy to talk more about DNS and help in any way possible.